While sustainability continues to become mainstream in supply chains, small farmers are often left behind. A fundamental basis of any functional strategy is to address the resilience of these smallholders.

The importance of a farmer’s ability to bounce back from shocks and stresses should be acutely obvious, especially in a post-COVID 19 world. The option to simply shift sourcing to other suppliers or regions may not be viable when disruptions are large or widespread. The good news is that it’s not difficult to add resilience to your current strategy. A recent COSA study shows how a few key resilience metrics can reveal important and actionable insights.

So, what factors make a household or community resilient? For many years, resilience was an inexact field and the lack of consistent guidance or standardized understanding of metrics plagued researchers and led to very high costs. Lengthy, complicated projects, plagued by academic and difficult-to-use findings, turned a good idea into something inaccessible thus useless to most projects or supply chains.

It would be unfair to fault organizations for not looking at farmer resilience as part of their sustainability programs before now. Until very recently, there were no simple or practical ways to measure small farmer resilience. That has changed. With the support of the Ford Foundation, COSA has played a leading role in shifting resilience measurement for smallholders from conceptual to pragmatic. We convened practitioner experts such as Lutheran World Relief, International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Conservation International, Sustainable Food Lab SFL, Catholic Relief Services, and Root Capital) in a Resilience Working Group and distilled highly functional indicators and metrics from their collective experience and from the best existing literature on the subject.

We undertook to simplify resilience measurement, standardize key indicators, and reduce costs. Our goal was to have more accessible resilience measurement so that all kinds of users could finally get fast and actionable results at a fraction of the previous cost. With the working group, we developed a foundational Resilience Measurement Tool including standard resilience indicators for farm households.

We tested the work in different settings from Syria and Nicaragua to Peru and Kenya.

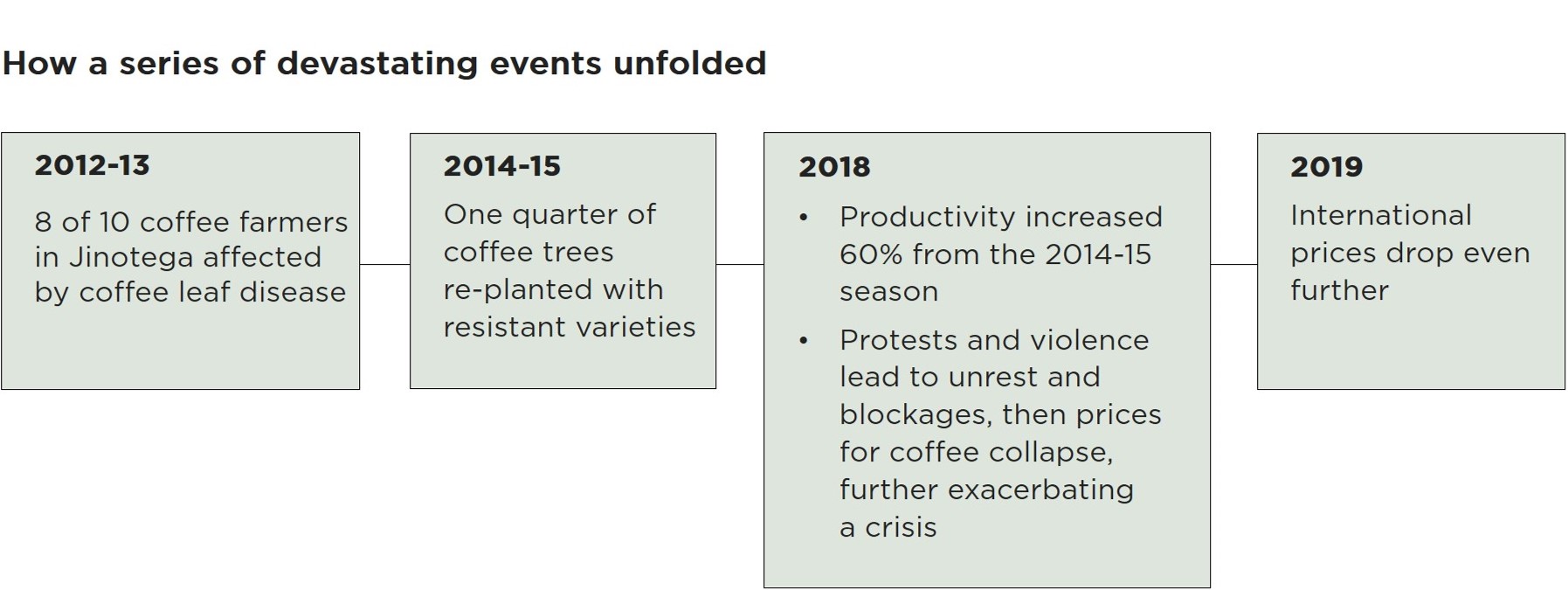

A recent COSA study offers fresh evidence for why understanding farmer resilience offers practical value. Using the basic set of 11 key resilience indicators, we assessed small farmers in Nicaragua who, from 2015 to 2019, faced one unexpected shock after another. Just when vulnerable farmers thought they were overcoming one major challenge – widespread coffee leaf disease – they were hit with a double blow in the form of civil unrest and then significant price declines. Against this backdrop of diverse setbacks, we set out to identify the most vulnerable groups, estimate farmers’ resilience, and explore the role of resilience in recovering from a shock.

The uncertainty produced by these shocks forced some farmers to migrate. Of those that remained, some fared better than others. Analysis suggests that farmers’ ability to cope with risk is strongly correlated with specific short-term preparedness strategies such as the use of good agricultural practices, soil and water conservation practices, and certainly diversification strategies. We also tested social safety nets related to finance and health.

Despite the significant effects of concurrent shocks, farmers with higher resilience scores performed significantly better. In fact, we observed that the higher the resilience level of the farmer, the higher the probability of recovery. Furthermore, this is an exponential effect; the more resilient you are, the more likely that a minimum increase in resilience will imply a higher probability of recovery.

When the factors that contribute to a farmer’s resilience are understood, companies or governments can target investments in the key drivers that enable households and communities to better face shocks and prepare adequate response plans. Getting real-time, accessible resilience information is not complicated; it can be as simple and low cost as including the basic set of 11 resilience KPIs into existing sustainability M&E programs. More comprehensive approaches are also readily available with a core set of 27 indicators. For more rigorous studies, the COSA resilience working group identified a full set of 76 resilience indicators that are available to anyone as a public good.

Others are contributing to the science of resilience. USAID’s Feed the Future Learning Community, with climate scientists from the CGIAR network, used COSA’s work, especially the farm-level indicators, in its USAID field guide. The Resilience Measurement Community of Practice (RMEL), with more than 90 organizational members (including COSA), also aims to strengthen good practices and the evidence base for resilience investments.

Value chain stakeholders and governments are searching for ways to make a difference. USAID writes that “to track progress against resilience objectives, companies will need to regularly monitor the conditions on the ground. This will include … monitoring activities put in place to build resilience within farming communities.” We could not agree more.

There is more work to be done to integrate household and community systems for a clearer picture of resilience. But for any business or NGO working with smallholders, resilience data points out strengths and weaknesses and provides clear direction for how to effectively target resources to help families prepare for and react to stressors and shocks in ways that limit vulnerability and promote sustainability.

Learn more about COSA’s resilience toolkit for systematically identifying and measuring the specific elements that build resilience.