Over the years, the Committee on Sustainable Assessment (COSA) has conducted dozens of experimental and quasi-experiment impact assessments in countries around the world. COSA employs the most rigorous methodologies available to better understand the social, economic and environmental impacts of agriculture in the belief that credible evidence of what works and what does not will lead to more sustainable practices. One of the ways that COSA pursues its goals is by conducting statistically significant surveys informed by detailed qualitative research that starts with development of a theory of change and is validated through wide-ranging stakeholder interviews.

We aimed to find out if Producer Organization (PO) management truly affects farmer performance in the way that typical theories of change hypothesize.1 Producer organizations, according to the FAO, involve farmers and other participants in producing agricultural products organizing groups to provide beneficial services including: enhancing access to and management of natural resources; accessing input and output markets as well as information and knowledge; and facilitating small producers’ participation in policy-making processes. All six POs in this study were farmer cooperative societies organized according to Kenyan law.

Focus group led by COSA research partners in October 2015 with members of one of the producer organizations involved in the Kenya impact evaluation

Recently, COSA was selected to conduct an impact assessment of an intervention with coffee farmers in western Kenya. In this work, we combined results from a random sample of 720 farmers from 6 POs with information from interviews with the management of those POs. We constructed indices that reflected the generalized theory of change for strengthening the PO’s ability to improve the lives of their members. These indices provided an intuitively understood picture that compares PO performance levels and allows for comparison to farmer’s performance. In short, we identified a baseline to allow us to measure whether POs really make a positive impact on farmer’s market access, knowledge sharing, input to policy making and their overall profitability.

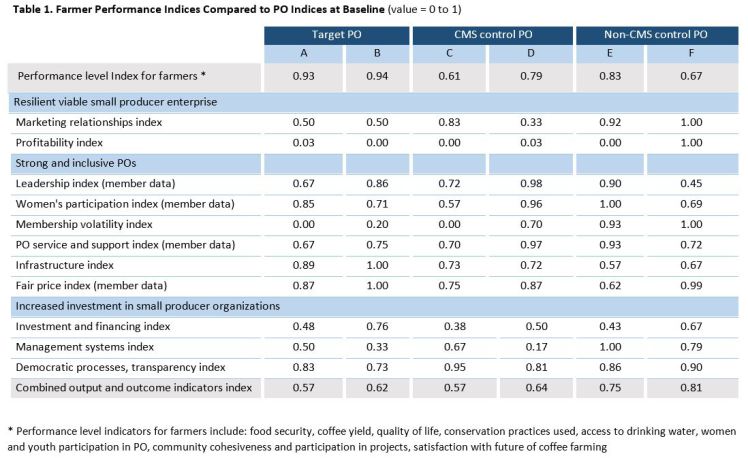

What we found was that there is little relation, in this sample, between what typical theories of change present as optimal PO attributes and farmer’s performance. The indices presented in the table below show that the target POs that rank lower in the indices of transparency and democratic process, gender inclusion, and business planning ranked higher on performance indicators for their farmers.²

Each index in the table expresses numerically only how the PO ranked compared to other POs, the peer group. The indicators selected were chosen to provide a sense of performance against dimensions of a theory of change regarding POs consistent with those of major standards bodies. For example, indices of performance to support development of “Strong and Inclusive POs” are: leadership, women’s participation, membership volatility, PO services and support and infrastructure. In general, from PO management, we learned attributes such as membership size, services provided, governance structure and rules for operating the PO. From farmers, we gathered evidence of impacts such as household food security, productivity, quality of life and so on (see the more detailed list beneath the table). The farmer survey also allowed farmers to express their perception of the value of services their PO provides, as well as their trust and participation in the PO. These ratings are incorporated into the index calculations.

This project looked only at one point in time, the baseline for the intervention being assessed. While the results suggest further investigation into what attributes build strong POs, the number of POs sampled is not large enough to reach any final conclusions. In the future, we will compare our preliminary results to data collected in three years in the same location. We will additionally look for opportunities to repeat our work in other locations in order to strengthen our understanding of what attributes make strong POs.

More than 1 billion people world-wide belong to some form of PO. While needing data from more POs and their members to be conclusive, this work suggests that we may need to rethink our assumptions about how these organizations improve the well-being of their members.

[1] Various theories of change hold that POs’ ability to improve their farmers’ lives depend on attributes such as transparency, democratic processes, good management systems, and gender inclusion.

[2] Farmer performance data is gathered independently and directly from farmers.

Originally published on The Global Forum for Agriculture Research.