Synopsis: In their simplest forms, Responsible Sourcing requires meeting or complying with accepted levels of ethical or responsible practices in areas such as human rights or pollution whereas Sustainable Sourcing goes beyond compliance to engage and improve the conditions of sustainability that can include areas such as dignified livelihoods or climate-smart practices.

Responsible Sourcing or Ethical Sourcing can be claimed when a company and its supply chains work to mitigate risk and avoid harm by meeting established (published and transparent) principles and specific measurable compliance criteria.

Alan Jope, Unilever’s CEO, believes this is a basic requirement for business, noting that “Behaving with integrity, day in and day out, is a non-negotiable”. But operationalizing the concept of integrity takes a few steps to ensure the clarity and effectiveness of the concept. Responsible Sourcing thus typically engages at three levels:

- Prevention – engaging clear practices, knowing suppliers, and actively pursuing a culture of integrity to diminish risks of poor practices or violations

- Detection – ensuring a transparent working system to detect violations with active data-driven assessment

- Response – confirming adequate policies and tools to effectively investigate and take swift action whenever necessary.

3 Steps to Responsible Sourcing

- Transparent & measurable compliance – Responsible Sourcing must be able to demonstrate that the product or service is sourced from responsibly managed resources and responsible suppliers that comply with transparent measurable criteria. To be credible, these criteria should align with global best practice as defined within relevant international norms and accords such as the ILO or the GHG Protocol.

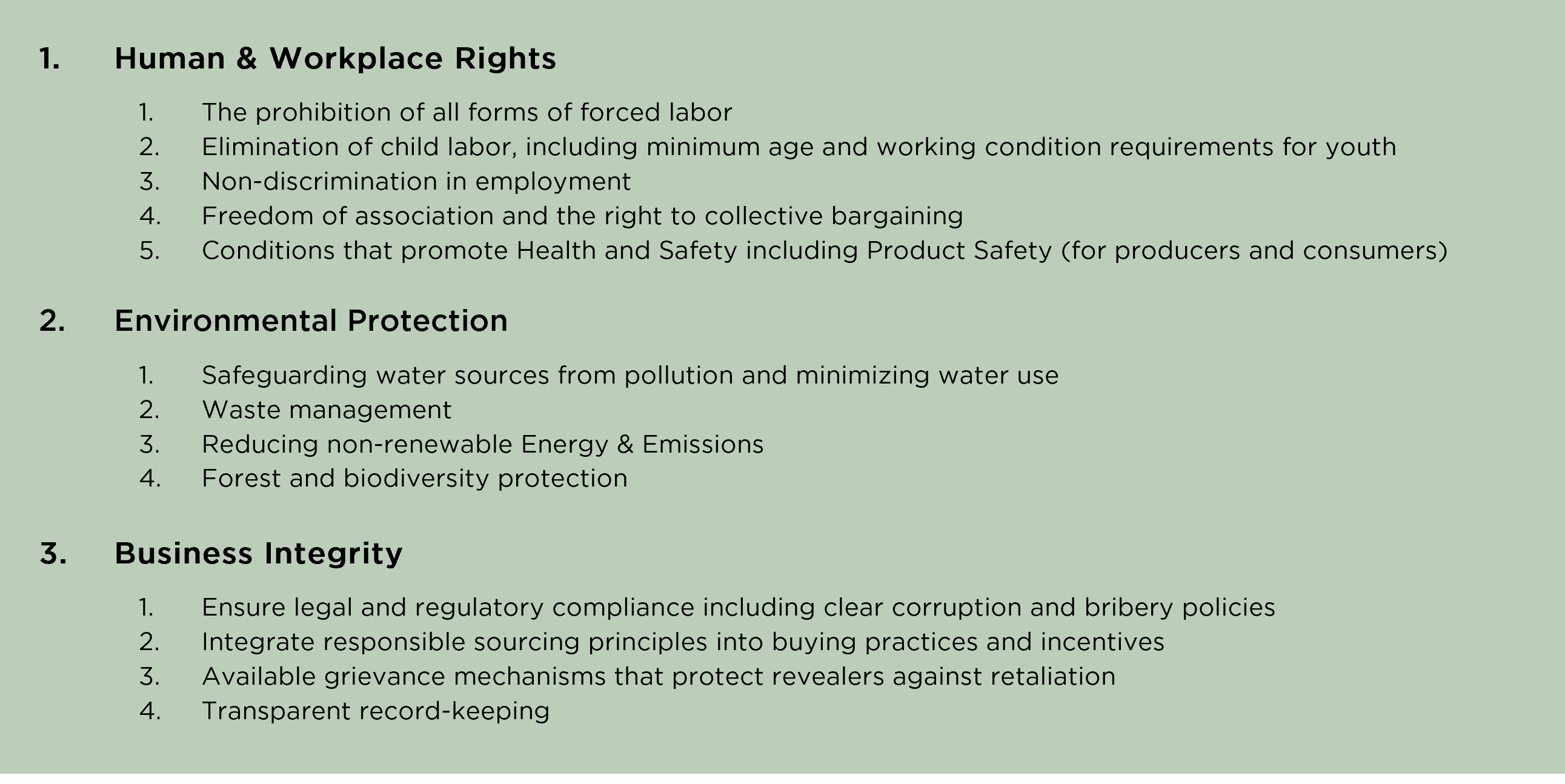

These should cover at least the key areas of human and workplace rights, environmental protection, and business integrity as outlined in Box 1[1]

Box 1: Key Areas of Compliance in Supply Chains (Not an exhaustive list)

- Traceability – To connect metrics or KPIs it is necessary to have traceability or knowing who the suppliers are. Opaque supply chains, where some suppliers are unknown, prevent claims of responsible sourcing. Where supply chains include small farmers, alternatives to tracking each farmer are available.[2]

- Assurance mechanism – The credible demonstration of responsibility must include reasonable and verifiable means of assurance to demonstrate some functional form of data monitoring and verification that minimizes the risk of misrepresentation or fraud. Such assurance balances the need to keep costs realistic, with the need for credible data and due diligence. Multiple sources of data may be integrated to achieve this balance, including assessments completed by suppliers themselves, e-verification of uploaded documents and other information, map overlays (such as deforestation maps), and some field audits.

Sustainable Sourcing includes all the aspects of Responsible Sourcing and goes beyond it.

A vital distinction of Sustainable Sourcing is that it is less transactional and more engaged toward a common purpose. It not only seeks to avoid harm but also to engage in improving the performance of the supply chain and its members on key social, environmental, and economic factors related to improving the lives of people and the health of the planet. To paraphrase the philosopher-economist Kate Raworth: this is not just doing less harm but doing more good.

This can be achieved by starting with a certain level of “knowing” that goes beyond simple traceability to having some awareness of the circumstances of producers, their environment, and the conditions where they work in fields and processing plants including any affiliated functions (inputs, transport, etc.). Therefore, it requires determining how the related key Social, Economic, and Environmental impacts of the supply chain are sustainable or getting there. Appendix 2 offers some of the main topics that are typically covered.

There is a certain continuum of factors or distinctions that often become evident as companies progress from Responsible Sourcing toward Sustainable Sourcing. These generally include:

- Being Aware of sourcing or compliance issues that affect good practices

- Tracing supply chain products and suppliers

- Becoming Committed tangibly to suppliers and sustainable sourcing practices

- Monitoring Performance on sustainability factors in supply chains

- Actively engaging to create and understand the Impact of its sourcing or programs

Appendix 1: Approaches to Responsible Supply Chain Principles

- Business Integrity: OECD, International Chamber of Commerce, Unilever

- International Labor Organization Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work

- Responsible Sourcing policies from ABInBev, Firmenich

Appendix 2

Various themes can be relevant and the most common include the following categories:

COSA develops metrics fully for all applications. For the basic suite of sustainability indicators see both:

- COSA’s Performance Monitoring Master List

- COSA’s expanded set of Impact Assessment Indicators

- COSA’s Resilience Indicator Library

- COSA’s Producer Organizations Indicators

[1] For example, a vetted producer organization, such as a cooperative, may serve as complying when it can demonstrate that it tracks and manages member compliance and non-compliance with globally accepted responsible practices that a company clearly and explicitly espouses i.e. no forced or child labor or no banned herbicides or pesticides. Similarly, if farmers carry certification to an accepted standard, that can serve as a trust proxy for knowing the farmer.

[2] For example, a vetted producer organization, such as a cooperative, may serve as complying when it can demonstrate that it tracks and manages member compliance and non-compliance with globally accepted responsible practices that a company clearly and explicitly espouses i.e. no forced or child labor or no banned herbicides or pesticides. Similarly, if farmers carry certification to an accepted standard, that can serve as a trust proxy for knowing the farmer.

Leave A Comment