Published in Coffee & Cocoa International, November 2019

Responses to problems in supply chains such as child labor need companies to go beyond ‘yes-no’ checklists and stop penalizing farmers. A more holistic approach is required that actually addresses the problem.

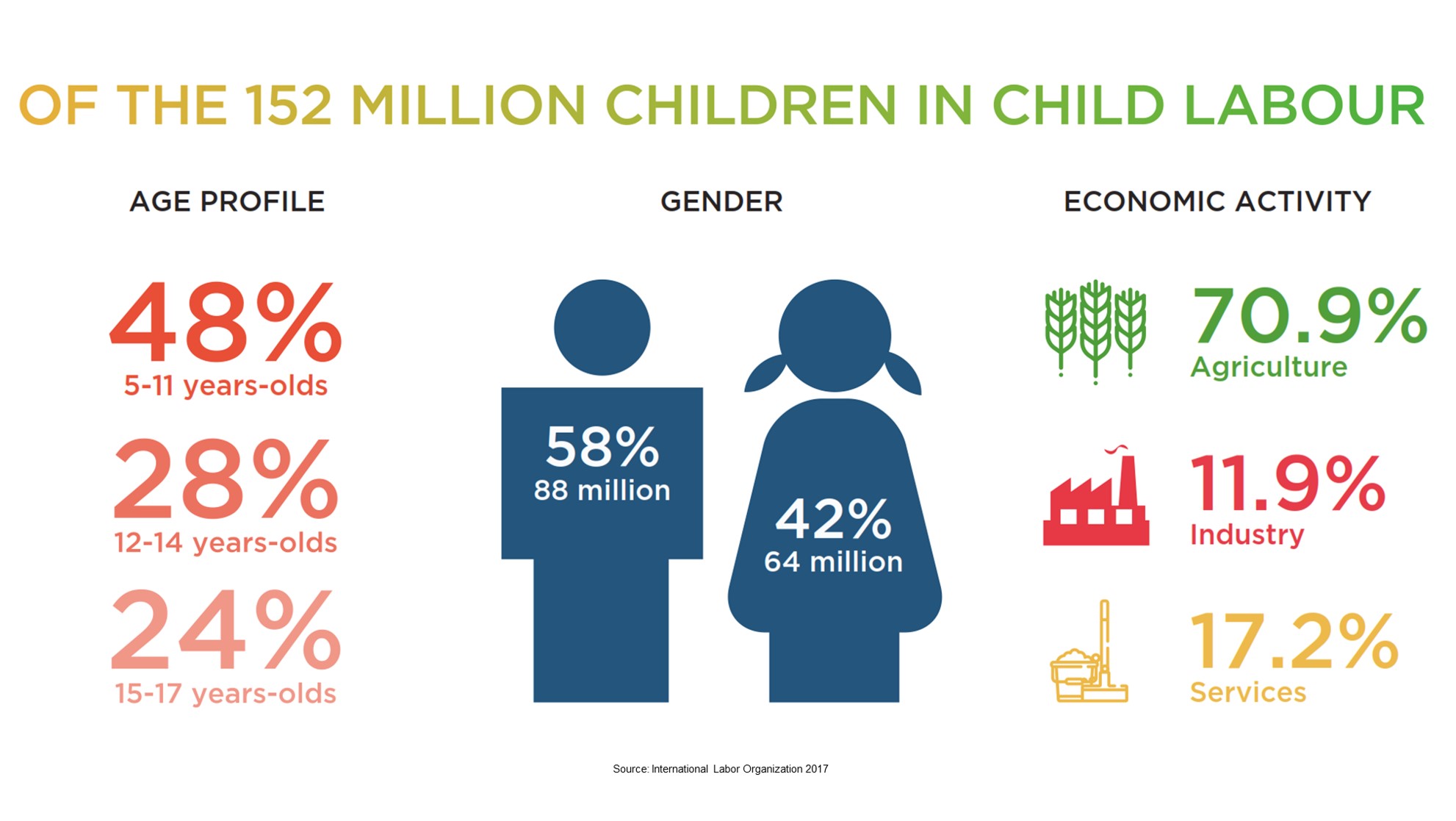

When child labor is discovered in a company’s supply chain, panic can ensue. And rightly so: not only is the nature of the problem appalling to us, the sheer number of children affected may be as big as the combined population of the United Kingdom and Germany. But are we taking these children as seriously as if they lived in the UK or Germany?

We have reviewed the different streams of ideas on this topic and offer some insight on what may be the most promising ways to go beyond just beefing up compliance or aiming anemic program efforts toward it.

When child labor or issues of great concern such as banned pesticides are discovered in a company’s supply chain, managers often react to contain the problem. They may want to determine who is to blame as well as distance the company from the issue and the suppliers. But with today’s emerging consciousness about such problems, there are smarter ways to prepare for and respond when disturbing conditions are found.

Consider that, in poor supply chains (usually smallholders) the best course for thoughtful companies is not to back away and may instead be to use the opportunity by choosing to engage the problems head-on. Does that take courage? You bet.

Not sourcing from those suppliers has not worked and often drives the problem underground. Clearly, our business solutions are not making enough of a difference as 152 million children are in child labor globally, with 73 million of them engaged in hazardous work that directly endangers their health, safety, or moral development. In cocoa, where the topic is often studied, credible reports suggest that the standard array of efforts have not made a substantial dent. It takes something more to make a profound impact.

Taking a stand to face and address the issues has the potential to powerfully alter the problem and the perception at the same time. What practical steps can a business take to get results?

Leading experts suggest that by understanding the context that leads to non-compliance, we may open ourselves up to deeper and more meaningful engagements with producers that can produce big sustainability wins. For brands and companies with the courage to take the route of engagement, this presents a powerful opportunity to differentiate themselves in the sustainability space and craft a compelling new narrative that speaks of a brand with a big heart, and a real commitment.

“News travels fast and bad news travels at lightning speed.”

– Cath Hill, Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply1

We know that seemingly intractable problems such as poverty, modern slavery, child labor, and deforestation are minefields for firms (and their supply chains) who are often ill-equipped to deal with them. These risks are not easy to avoid for even the most diligent companies that handle coffee, tea, cocoa, palm oil, cotton, sugar, timber, and other commodities. Leading companies often begin their efforts to minimize the risk of such scenarios by assuring that their suppliers comply with a real code of conduct, not just the outdated yes-no checklist. Most brands and major buyers however, are realizing that compliance checks are simply not enough. Responsible sourcing managers are beginning to use their code of conduct more as a needs assessment that identifies the opportunity to address and resolve challenging findings.

Experience suggests that this approach is best taken with a locally savvy partner, usually a civil society organization. Sophisticated companies like Mars have announced plans to work with certifiers and suppliers to address child labor challenges through community monitoring and intervention schemes2. Nestle is extending its child labor monitoring intervention with the International Cocoa Initiative’s Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation System (CLMRS)3, designed to address child labor issues through an array of localized actions as basic as helping children obtain birth certificates to continue their education, bridging classes for children that have dropped out of school, and sending local facilitators into homes to talk with parents and children. Through its Cocoa Life program Mondelēz has made annual gains in establishing local Child Protection Committees, and it also implements the ICI’s Child Labor Monitoring and Remediation Systems4. Ferrero too has partnered with NGOs including Save the Children and local cooperatives, among others5.

More often, however, when noncompliance in issues such as child labor or banned pesticide use is found, company responses only touch the surface. Even worse for poor communities, they may replace ‘failed’ suppliers with new ones, a common practice to meet compliance standards. Some of these may simply be more adept at hiding their non-compliance. Other companies offer offenders a probationary period to resolve the issue. From a brand perspective, this is a reasonable reaction to eliminate poor conduct and protect a brand’s reputation.

But often suppliers with failing grades are unable to comply. In poor regions, some cannot afford to incur the necessary cost that comes with real compliance. As researchers Hannibal and Kauppi recount, “If you impose criteria which aren’t…feasible…all you are doing is throwing [the supply chain actors] out of the market and denying them (the opportunity) to develop…6”

In the case of children, they may go underground into domestic servitude or other sectors such as tourism. Supply chain codes of conduct or compliance checklists do nothing to address the deep poverty that forces children into labor. Simply identifying the problem does not solve it and may worsen it by eliminating an option.

There are no easy answers. A ban on child labor, for example, “requires a child-centered approach addressing the enablers and push factors” says Aarti Kapoor, Managing Director of Embode and a thought leader on human trafficking and child labor. “The point is to reduce child labor [or other non-compliance], not to hide it or push it under the fence.”

When serious violations occur that are clearly willful — such as plantation forced labor or a polluter that has other options — a strong response is appropriate and such violations should be fully reported. While strict rules are meant to create an incentive for compliance, when they make the problem worse, it is necessary to ask: is this really “responsible” sourcing? As a 2015 report in The Guardian7 suggests, a categorical ban on child labor is “a policy with its head in the sand, one that will overshoot the intended goal of improving the lives of children workers” if not thought through properly.

Kapoor and others have made distinctions between children occasionally contributing labor in a safe and parent-supervised manner and child labor that robs children of opportunities and exposes them to dangerous practices, abuse, and manipulation. Certification bodies such as Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade are also adjusting their understanding of failed compliance. Rather than outright prohibition and sanctioning they can now apply due diligence approaches and remediation that they find have a higher impact than only prohibition.

S&D Coffee, Inc. – a supplier of major US brands with thousands of farmers supplying their RAIZ coffee line – gives farmers a period of time to take corrective actions, where non-compliance is found by auditors (except in the most egregious findings). In some cases, S&D supports the farmers directly to address their issues. For example, to help farmers avoid contaminating waterways with processing effluent, they have provided materials and training to build catchment ponds so they could comply with S&D’s codes. This commitment was not only recognized by some of S&D’s major clients but also improved their relations with local suppliers and farming communities.

Traceability protocols are the foundation for understanding the functional realities of communities and suppliers embedded in the supply chain. Some of the world’s largest confectionary companies “still cannot identify the farms where all their cocoa comes from, let alone whether child labor was used in producing it8.” With the increasing accessibility of agile data systems that minimize effort and cost while still lending themselves to verification, companies can now learn about the social characteristics associated with farms.

Ensuring that workers are paid a living wage in the first place is a major incentive that can obviate the need for children to work, and hence can be a tenet of responsible firms. Groups like the Living Income Community of Practice9, led by GIZ, ISEAL Alliance, and the Sustainable Food Lab are working to help determine what a living income in different places is, and promote that for small farmers.

We all admire a caring and courageous company. Even though an intangible like moral courage or caring may not always show up on a company’s valuation it may capture consumer hearts and perhaps market share. One thing is certain, children have been waiting for such moral courage for too long.

- McClelland, Jim “Human rights falter in grey areas of procurement policy.” Raconteur: Future of Procurement. April 6, 2019 https://www.raconteur.net/future-procurement-2019

- Ionova, Ana, “Mars aims to tackle “broken” cocoa model with new sustainability scheme.” Reuters, September 19, 2018 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cocoa-mars-sustainability/mars-aims-to-tackle-broken-cocoa-model-with-new-sustainability-scheme-idUSKCN1LZ1DZ?il=0&utm_source=reddit.com

- https://cocoainitiative.org/news-media-post/ici-nestle-extend-child-labour-monitoring-coverage-to-over-11000-cocoa/

- https://www.cocoalife.org/the-program/child-labor

- https://www.ferrero.com/news/Ferrero-Takes-Action-Against-Child-Labour

- Hannibal, C. and Kauppi, K. “Third party social sustainability assessment: Is it a multi-tier supply chain solution?” International Journal of Production Economics, Sep 7, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.08.030

- Wijen, Frank. “Banning child labour imposes naive western ideals on complex problems.” The Guardian: Aug 26, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/aug/26/ban-child-labour-developing-countries-imposes-naive-western-ideals-complex-problems?CMP=share_btn_link

- Whoriskey, Peter and Siegel, Rachel: “Cocoa’s child laborers” Washington Post, June 5 2019 https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/business/hershey-nestle-mars-chocolate-child-labor-west-africa/

- https://www.living-income.com

Leave A Comment